How therapy and community practice can be spaces where the body remembers what systems forget

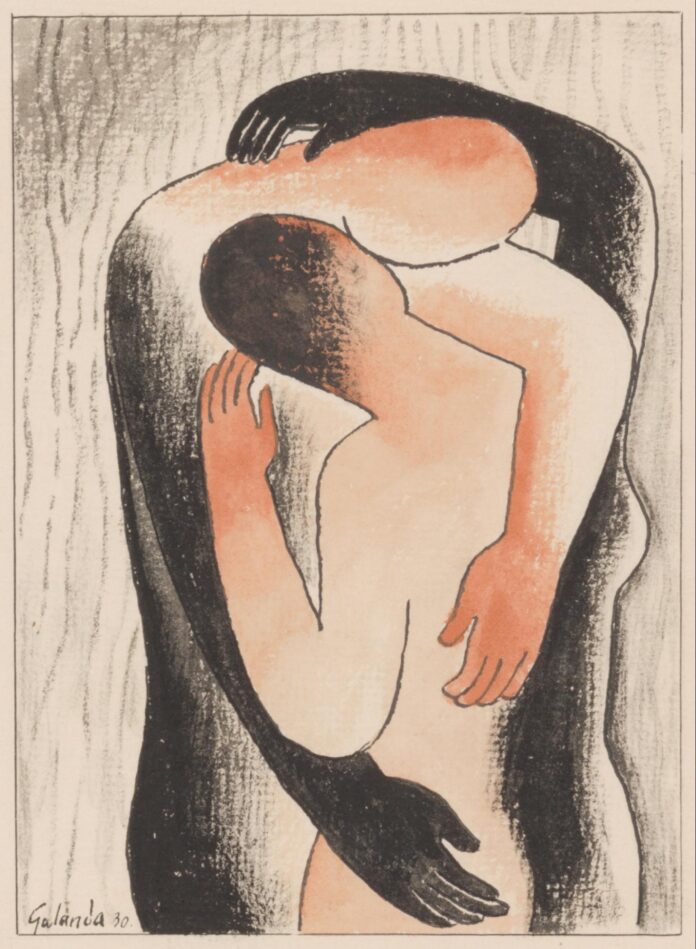

In therapy rooms, classrooms, and community spaces, I witness how bodies flinch, soften, hold, and reach, gestures that speak louder than policy. For those of us working through social-justice-centered mindfulness and the body, the body is not simply a site of calm or awareness, it is where history lives. Through our breath, posture, and pain, we inherit caste, gender, and privilege, and we also unlearn them.

In my counseling work, mindfulness is not an intervention but a stance, a way of being with the bodymind as it responds to the world. Both therapist and client participate in this relational noticing, each movement of awareness mirroring the other. Like a fractal, what happens within one body reflects the collective, and each act of noticing ripples outward into social worlds.

Over the past two decades in the field of psychology, through my work as a therapist, supervisor, and teacher, and as part of the collective at Pause for Perspective, the mental-health organization I founded, I both – hold and have been held, taught, and transformed by this understanding. What began as a clinical application of mindfulness slowly became a practice of liberation. As I deepened my engagements in queer, feminist, and anti-caste training, and as narrative practice and social-justice-centered counseling psychology began to shape my worldview, I saw something shift.

When I set aside mindfulness as a psychological tool, what remained was life itself. People’s bodies were already responding, reaching for safety, connection, and dignity.

It was in this recognition that I began asking people how their bodies respond to systemic privilege and oppression. This is where Embodied Social Justice in Counseling was born, a lived-experience-centered articulation of the body as a site of liberation, protest, and resistance.

And so I began to wonder:

- What might our bodies be saying about the worlds we live in?

- How do they show us what we can no longer carry?

- How do they remember what we deserve?

From those questions, and from listening to people’s stories over the years, three patterns began to emerge.

The body shows itself as a Site of Liberation, of Protest, and of Resistance. Each is different, yet all belong to the same rhythm of remembering.

Body as a Site of Liberation

Liberation does not always look like freedom. Often, it looks like the slow return of breath, a body remembering that it was never meant to live so small. In the work of embodied social justice, liberation unfolds in two movements: aliveness and displaying our right.

Aliveness

Aliveness refers to the embodied awareness of being present and connected to life, a sense of vitality that emerges when individuals begin to experience their bodies not as objects to be controlled or improved, but as living sites of knowing, sensing, and responding. It is the movement from disconnection to contact, from mechanical functioning to felt presence.

In counseling, aliveness often arrives when the body stops being treated as an object to be fixed and begins to be felt as a living, sensing being. Someone notices warmth in their chest after years of numbness, another pauses mid-sentence and whispers, “I can feel my body again.” These moments are not about wellness but about returning to life after long forgetting

When people connect to the body in this way, they begin to unlearn the stories that call their bodies lazy, weak, broken, or too much. They start to see that their breath, pain, and stillness are not failures but signals, reminders that the body has always been speaking. For some, this means letting go of internalized ableism or caste-coded ideas of worth. For others, it is simply the act of staying with a tremor instead of pushing through it.

I often witness this in therapy: a client who thought their anxiety was something to control begins to listen to it instead, someone living with chronic illness finds ease not in doing more, but in resting without apology. In those pauses, colors return, breath deepens, and life expands beyond survival.

In community, aliveness shows up as bodies leaning toward each other, sharing food, laughter, silence, an ease that does not need to perform strength. It is the moment we realize that being alive together, even amid injustice, is itself a form of dissent.

When I sit with others, I often ask:

- What does aliveness feel like in your breath, your skin, your posture?

- What part of you knows it is still here, even when the world denies it?

- What if being alive was not something to prove, but something to notice?

Aliveness, in this way, is both personal and political. It is the body remembering that it has agency, that it can still choose how to respond. Each breath becomes an act of self-definition, a way of saying, I am not an object of this world’s systems; I am part of its living pulse.

Displaying Our Right

If aliveness is the pulse within, displaying our right is how that pulse becomes visible together. It is the collective body remembering its place in the world, saying, We belong here.

I see it in community spaces when people sit together in shared exhaustion after speaking about caste, gender, or queerness, no one rushing to fix or explain, everyone simply staying. It looks like people singing protest songs, sharing food, or resting side by side after long work. Sometimes it is someone noticing a microaggression and another person stepping in, saying, “I can hold this one; you rest.” These gestures of care are not small. They are acts of display, the body showing that belonging is not granted by systems but practiced in solidarity.

When we gather, I am often curious about:

- What helps our bodies stay present together when the world would rather we disappear?

- How do we make room for each other’s rest and rage?

- What does it mean for a collective to display its right, to joy, to justice, to togetherness?

Liberation, then, is both inner and shared: the body remembering its aliveness, and communities displaying their right to exist together. It is not freedom from oppression, but the everyday act of being fully here, with one another, anyway.

Body as a Site of Protest

If liberation is the body remembering its aliveness, protest is the body saying no to what harms, silences, or distorts it. Protest does not always look like shouting in the streets, though it can. Sometimes, it looks like stillness, numbness, or refusal, the quiet ways the body protects itself from a world that demands it perform.

Freeze / Refusal to Engage

In counseling, I have seen this often. Someone begins to speak about violence or humiliation and suddenly goes blank. Their eyes glaze over, their voice softens to almost nothing. In older models of therapy, this might be called resistance or avoidance or even trauma that has stripped away all agency. I have come to see it differently, as protest. The body is saying, I will not go further into this until safety is restored.

In a world that rewards compliance, where marginalized bodies must constantly prove they are fine, functional, resilient, to freeze is to refuse performance. It is the body’s wisdom, not its failure.

I often ask, gently:

- What might your body be protecting right now?

- What feels too much to touch, and what would make it safe enough to stay?

- How has your body learned to say no when words could not?

This pause, this refusal, is sacred. It reminds us that survival itself is protest, that the body will not keep sacrificing itself just to be understood.

Refusal to Be Erased

Then there are moments when protest takes form as voice, anger, or visibility. A queer client once said, “I am tired of sounding polite when I talk about what has been done to me.” Another laughed sharply after telling a story of discrimination and said, “I think that laugh is my way of saying I am still here.”

In community spaces, refusal appears as returning to one’s own power. It is the moment a group falls silent after someone names caste violence, not because they are shocked, but because they are listening with their whole bodies, in compassion. It is when someone interrupts a conversation that is sliding into saviorism and says, “Hold on, this does not feel right.” Protest here is not chaos, it is clarity. The body knows when enough is enough.

In these spaces, I sometimes ask:

- What does your protest look like today, in voice, in silence, in presence?

- How does your body tell you when something has gone too far?

- How can we honor protest rather than rush to calm it down?

Protest, then, is not defiance for its own sake. It is the body’s way of saying, I will not disappear. Even when safety is fragile, dignity remains non-negotiable.

Body as a Site of Resistance

If protest is the body’s response to oppression, resistance is the body’s awakening to its own systemic privilege. It is what happens when we start to feel the gap between what our bodies have been granted and what others have been denied through caste, patriarchy, cis-heteronormativity, capitalism, and more. Resistance asks us to stay with that gap, not to collapse into guilt or rush to fix it, but to listen to what the body is learning about power.

Calling the Bluff of Privilege

Calling the bluff of privilege is when the body begins to see through its own comfort. It is when we recognize that what feels normal or neutral may in fact be ease afforded by caste, class, gender, or ability. It is not a moment of shame but of clarity, a bodily realization that says, this ease is unevenly distributed.

In counseling, I have seen this when someone notices how easily they take space, speak first, or move toward fixing pain they have not had to endure. One client said, “I realized I get to look away, others do not.” That moment was not self-blame, it was the beginning of change. When we call the bluff, we learn to acknowledge bias, stay with discomfort, and actively choose differently, whether that means listening longer, redistributing opportunity, or making room for other voices.

For therapists and community members alike, this practice is ongoing.

It is not enough to see privilege, we must work with it daily to interrupt its patterns in our bodies, conversations, and institutions.

Over time, this consistency of noticing, naming, and acting moves us toward liberation, toward the collective display of our right to live in equity and dignity.

Friction with Privilege

Friction with privilege is what happens when comfort begins to crack. It is the crossroads, the moment when the ways we have been taught to be in the world no longer fit, and the body knows it.

In therapy, this might look like a husband saying, “My wife does not listen to me anymore,” feeling wounded, not realizing that what is being challenged is not love, but the expectation of being centered. Or a colleague feeling defensive when their leadership style is called out as silencing others. Or an upper-caste client realizing their “good intentions” still keep them in control.

These are the moments when the body tightens, the chest heats, the jaw clenches. Something inside says, this feels wrong, but the wrongness is not about being attacked, it is about being asked to unlearn the ease that power affords.

Friction is that bodily distress, the moment we sense that the values or roles that once gave us stability are also what keep inequality alive. At that point, we stand at a choice, to fold back in, defend comfort, and force the world to perform for us again, or to stay with the unease long enough to call the bluff of privilege.

Sitting in this friction is not easy. It asks us to remain open even when our affection, identity, or belonging feel at risk. But this is where transformation begins, when the body learns not to flee toward comfort but to stay and listen to what discomfort reveals.

And here lies the liberatory potential, not only for those marginalized, but for all of us. When we let the friction do its work, privilege begins to lose its hold. We begin to move differently, relate differently, love differently. What once felt like loss becomes a kind of opening, a way of belonging that does not depend on dominance but on reciprocity.

I often ask:

- What feels like loss, and what if that loss is a doorway to fairness and freedom?

- What happens in your body when you stop defending your certainty?

- How might staying with discomfort be a practice of liberation, not just accountability?

Friction with privilege, then, is not the end of comfort but the beginning of connection. It is the point where the work of justice turns into the possibility of shared liberation for every body involved.

The Fractal of Embodied Social Justice Counseling

These movements, Liberation, Protest, and Resistance, do not come in order. They spiral. The same breath that softens in relief might tighten in anger a moment later. A body that learns to rest may soon feel the friction of its own privilege. This rhythm of softening, tensing, and reaching again is the shape of our work. It is the shape of being human inside systems that both harm and hold us.

Inspired by the work of Adrienne Maree Brown, I often think of this as a fractal, a pattern that repeats at every scale. What happens in one body reflects the collective, what happens in the collective echoes within each of us. When a client takes a deeper breath, a group somewhere can rest a little easier. When a community finds the courage to name harm, an individual somewhere might finally stop apologizing for existing.

In therapy, this means the work is not about solutions. It is about staying close to what the body already knows, the small tremors of truth that appear in silence, fatigue, laughter, and breath. In community, it means we learn to practice together, not by getting it right, but by listening for what wants to be remembered.

So perhaps the questions that remain are these:

- How can we listen to our bodies, and to one another, as if they are archives of everything we have survived?

- What happens when we treat awareness as a shared responsibility, not an individual goal?

- How do we keep remembering that even within oppression, life keeps reaching toward connection?

Embodied Social Justice in Counseling is not a method or a destination. It is a way of being, a daily practice of noticing, sitting with, and responding. It is the work of remembering that liberation, protest, and resistance live in the same breath, and that every time we pay attention to the body, we are also tending to the world.

The body remembers what systems forget

And when we listen, within ourselves, between each other, and across our communities, we begin to remember too

Aarathi Selvan

Aarathi Selvan Ph.D. (they/them) is a counseling psychologist, researcher, and founder of Pause for Perspective, a mental health collective based in Hyderabad. Their work centers Embodied Social Justice in Counseling, a framework that invites therapists, clients, and communities to understand the body as a site of liberation, protest, and resistance. Drawing from queer, feminist,anti-caste and disability justice paradigms, Aarathi’s practice bridges mindfulness, narrative approaches, and community mental health in India.