“I used to study and play around. There were so many trees around our house. Mango tree, guava tree. I used to sit under those trees and study. I would play around so much when my parents were there. The police brought me here when my parents passed away.”

This is the story of Riya, a young woman admitted to a government-run psychiatric hospital by the police. In India, it is still a common practice for police to admit people to psychiatric hospitals.

“I used to work. I was married and had a son. I liked listening to songs and playing football. I had many friends in my neighborhood. Now, I do not have any relations with anyone. I used to wander on the streets. So, the police brought me here.”

Suraj shared his story, mentioning that after the police brought him to the hospital, his social relationships ended. He added, “I did not tell my real name to the police because I have heard that once your name is recorded in police documentation, finding jobs becomes difficult.”

When Others Speak for You

From people living on the streets to vulnerable people living within homes – the police have the autonomy to decide for these people and admit them under psychiatric care. A court order is required for such admissions. People admitted by court order rarely have the opportunity to go back to their communities as there is no one to look out for them.

As soon as a person steps inside a psychiatric hospital, their stories are often stripped away from them. The person loses the right to tell their own stories as they are often told by doctors, psychologists, social workers, courts, and the police. Moreover, their stories are narrated from the lens of psychiatry, illness, abnormality, and deviance.

Stories of the Mad, by the Mad

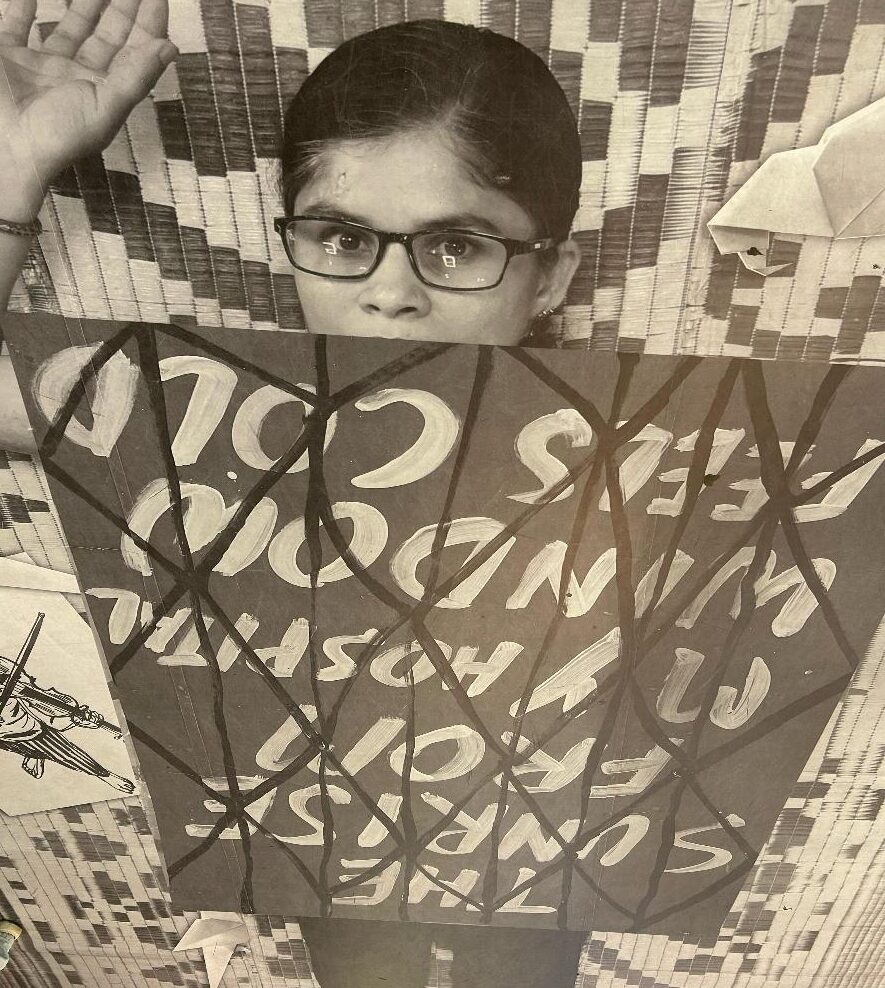

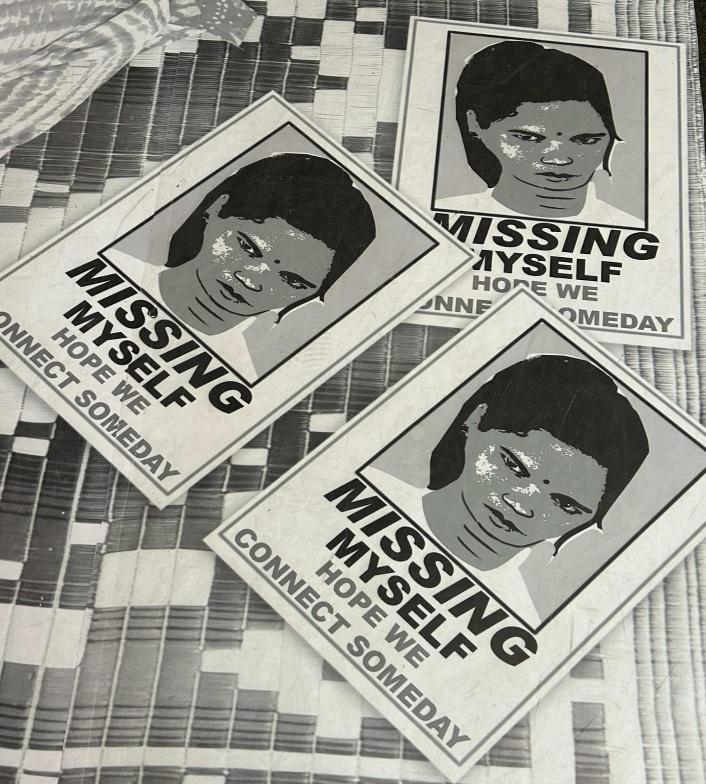

To restore their right to tell their own stories and to let them voice their multiple and alternative stories, Anjali Mental Health Rights Organization, a local NGO based in West Bengal, put together a public art installation. The installation was showcased in one of the busiest malls in Kolkata. By placing the installation in a popular mall, the exhibit asked everyday shoppers to pause, listen, and reflect—creating a moment of intimacy in a public space.

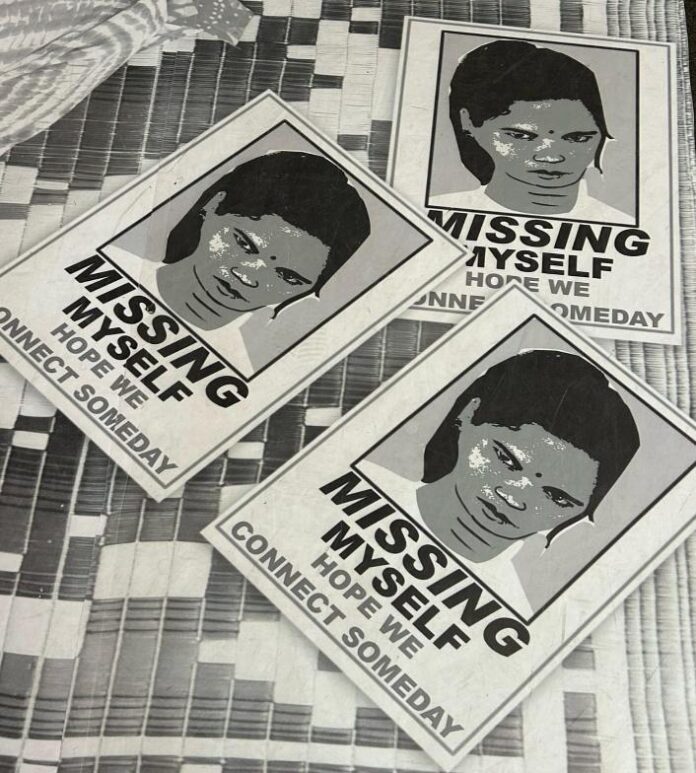

The installation consisted of a tree of stories, large photos laid on the ground, and QR codes alongside photos. The viewers scanned the codes to hear the full story as told by the people in the photos. Apart from people’s life stories, the installation also showed their narratives depicting their lived experiences of staying in the hospital.

Living in locked wards

After being brought to the hospital, people stay in locked wards. The iron doors only open for them to use the toilets. Such a restriction on movement completely cuts them off from the outer world.

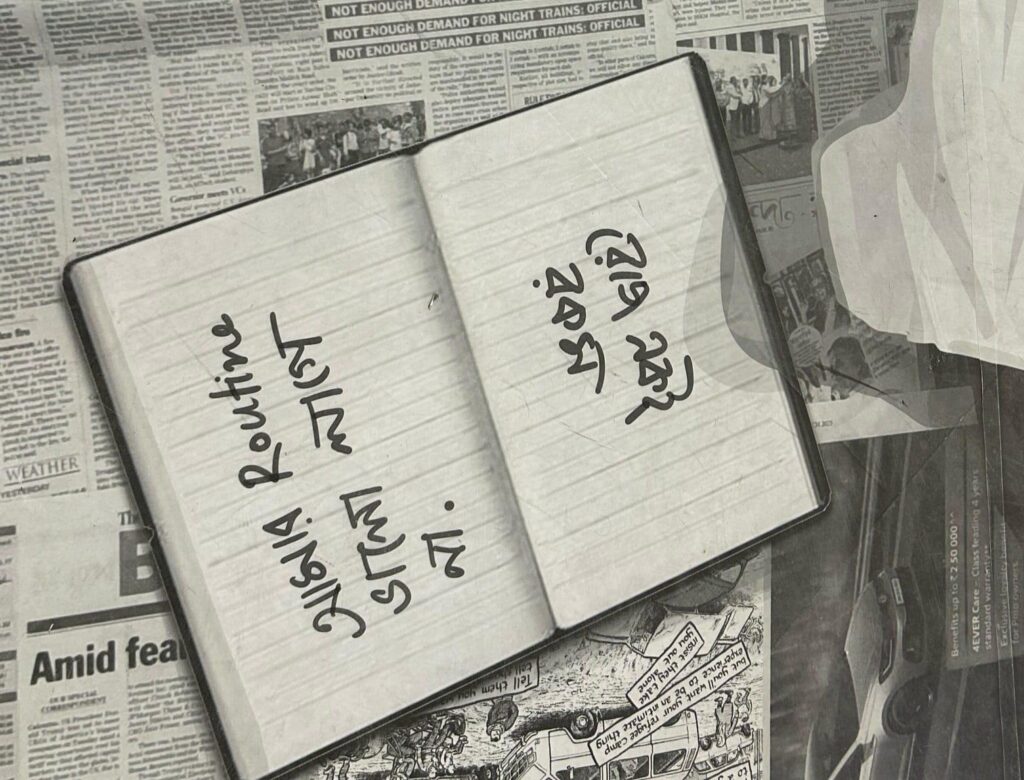

They do not have the luxury of freedom, dignity, or autonomy within the locked wards. They are required to follow a routine all day, which consists of waking up, eating, taking medicines, and sleeping again. The hospital hardly organizes any activities for them within the wards. Such a routine often creates a sense of boredom.

Outside the locked wards of the hospital, there seems to be a constantly moving world. However, within the wards, their life stays static. “Every day is the same. I do not like routine.”

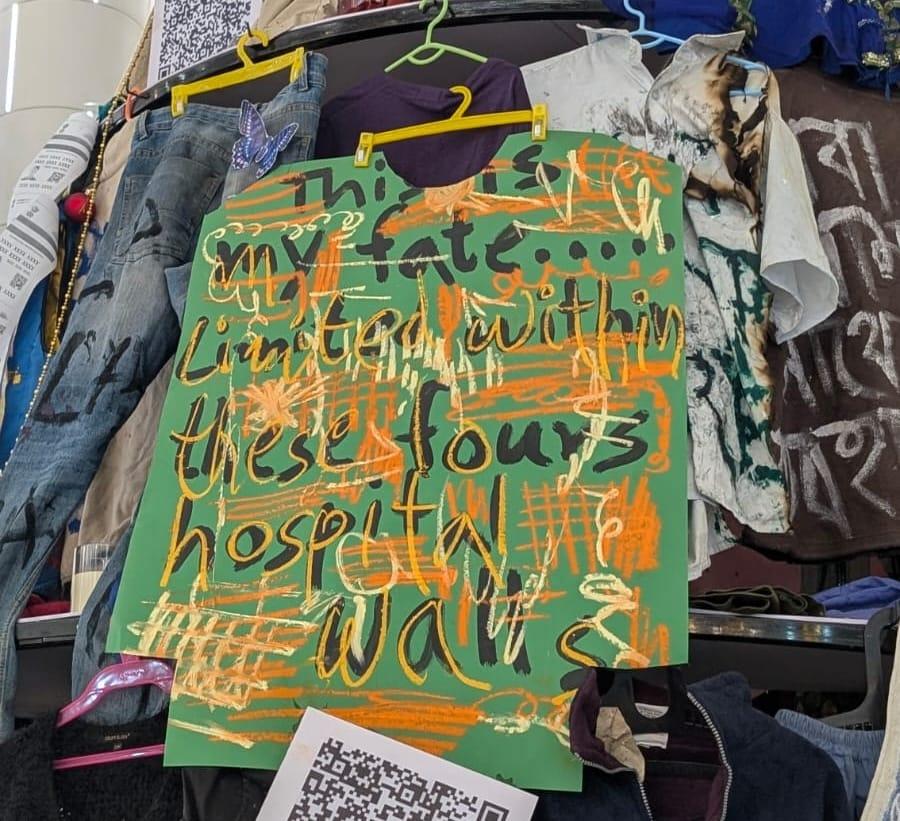

Living with the same routine for months and sometimes years on end forces them to accept this as their fate. An artwork read, “This is my fate, limited within these four hospital walls.” Within these walls of the hospital, their stories are forgotten, and identities are removed, reducing them to mere medical cases.

Alternative Stories of the Mad

In a restricted space where people’s voices are overpowered by the surrounding systems of psychiatry, law, and police – bringing forth their alternative stories is a radical act of resistance and empowerment.

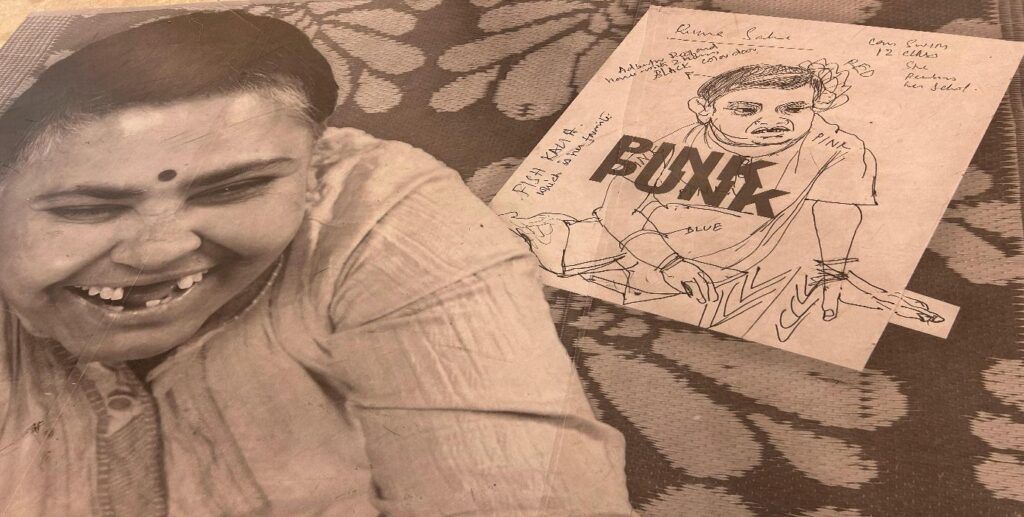

Wearing a big red flowered hairband, Ruma talks about all the flowers that she likes, counting them on her fingers. She tells how she used to go swimming. And then suddenly asks, “Will they take me home? They will take me home, right?”

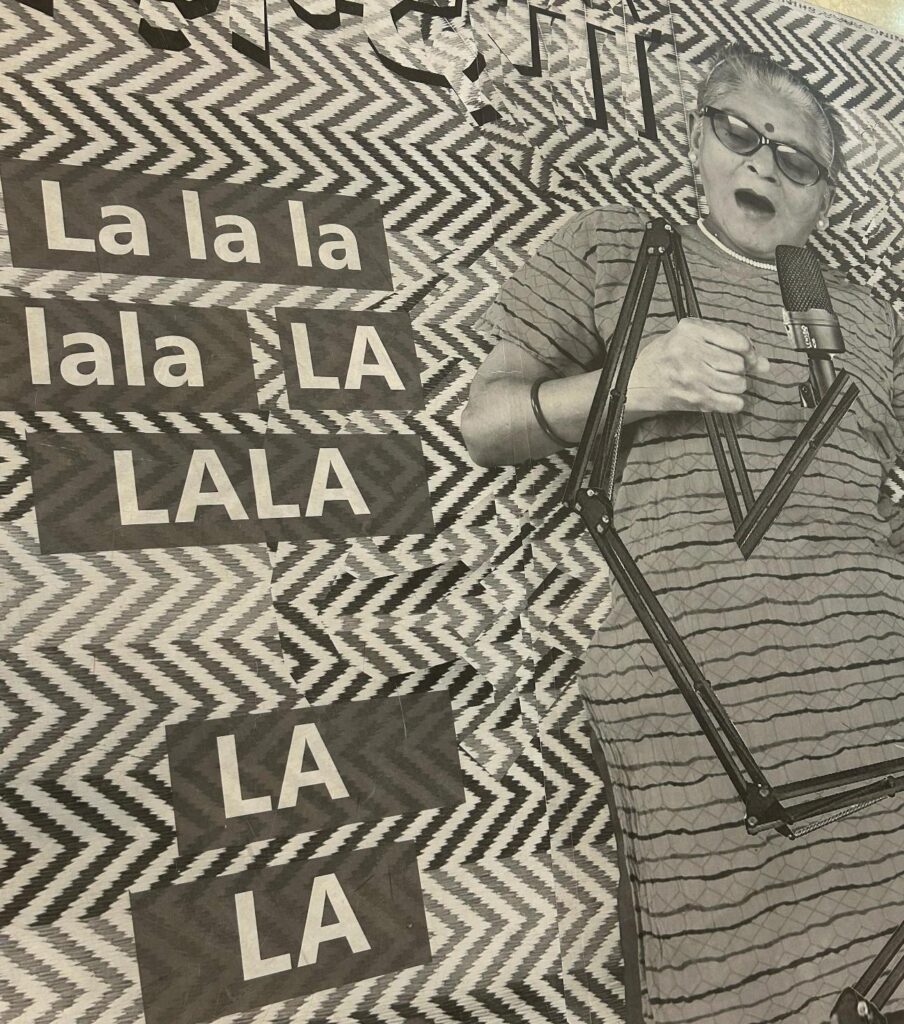

Flipping through her notebook where she has written the lyrics of various songs, Mitali sings, “Zindagi pyaar ka geet hai… isey har dil ko gaana padega.” (“Life is a song of love that every heart will have to sing.”) Talking about her passion for singing, she says, “I really love singing. I used to go to the music academy when I was younger.” Now donning very short grey hair, white dangling earrings, and a yellow kurta – Mitali looks enthusiastic and determined to learn more about music.

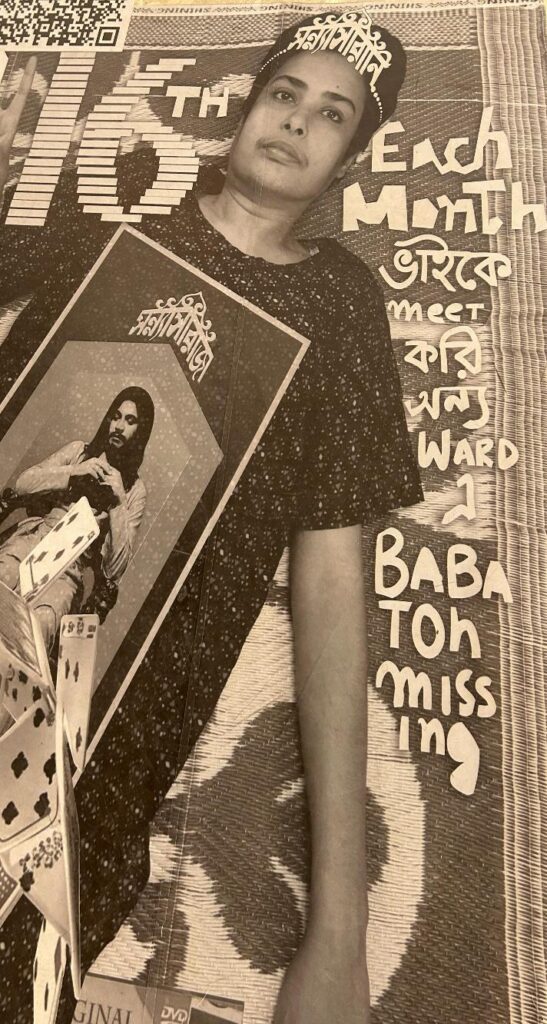

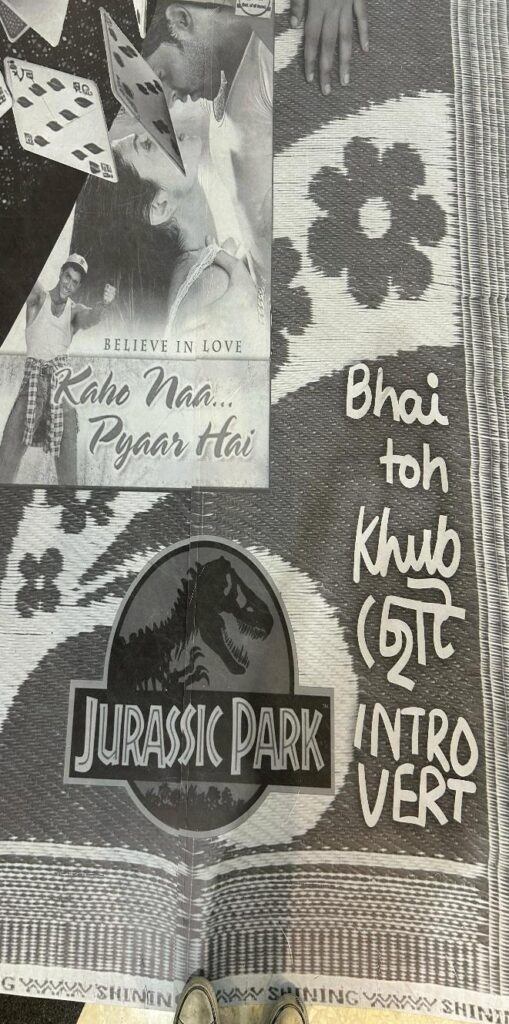

Sujata recalls the innocent fights she had with her brother. She says, “We used to fight for the TV remote. He wanted to watch cartoons, and I wanted to watch serials.” Further sharing her love for TV entertainment, she named the movies she has watched, adding that she saw the popular Bollywood movie Kaho Na Pyaar Hai, starring Hrithik Roshan, in a cinema theatre near her college. She also mentioned two Hollywood movies, Titanic and Jurassic Park, among the movies she has watched. Her brother has also been admitted to the same hospital in the male ward. She meets her brother on the 16th of every month in the other ward but continues to miss their father.

Life Worlds of the Mad

The outer world is quick to impose labels of illnesses on people living with different realities. As soon as they enter restrictive spaces of “treatment” for these labelled illnesses, their life stories are erased. Treatment regimens rarely include the stories of their life-worlds, which allowed them to survive and thrive outside of the hospital walls. From swimming, singing, and watching movies in theatres to studying and working – outside the hospitals, their lives looked similar to yours and mine. And, yet, the hospital, the treatment, the courts, and the police erase and take away from them what matters to them most – their identities, their preferred ways of being, and their life narratives that allow them to be.

To bring such stories into the public domain in the voices of the people who have lived and owned these stories is a powerful act. Inviting people shopping and enjoying in the mall to witness this art installation calls for a quite slow revolution where madness won’t be marginalized. It would take the space that it rightly deserves!

Neha Jain

Neha Jain is a doctoral scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Kanpur. In her doctoral work, she is exploring institutionalized and de-institutionalized mental healthcare settings in India to understand the nature of care and recovery in mental health through the experiences of various stakeholders. She is also a counseling psychologist trained in trauma-informed therapy and works through an attachment lens with people in their early adulthood years. Apart from therapy and research, she loves reading personal newsletters and listening to Desi rap music.