A Chance Encounter

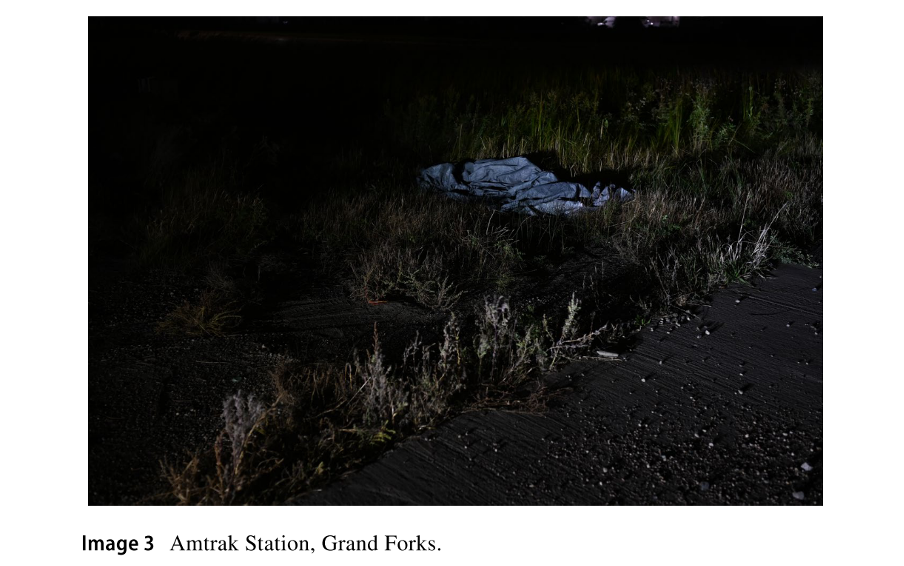

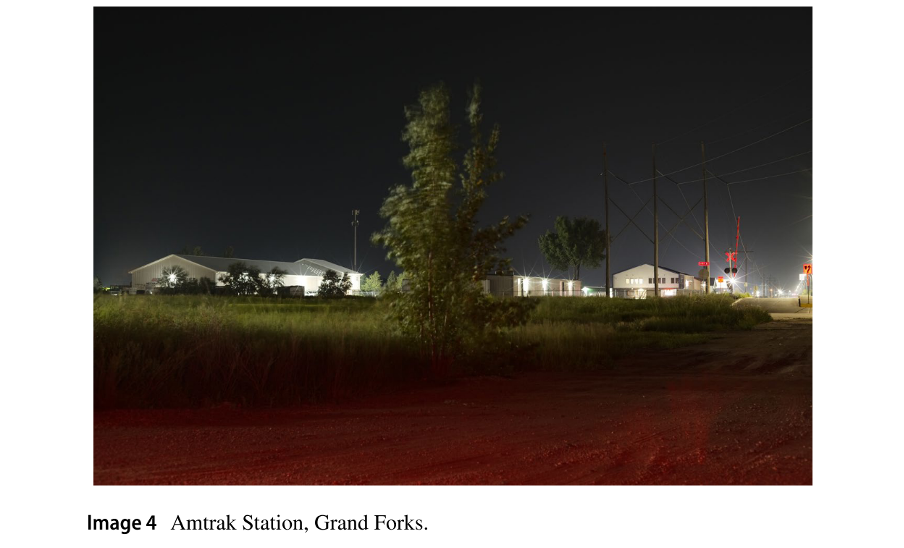

On a bright and warm Friday morning, Gaurav decided to take a detour to the Amtrak station before going to his lab, where he works as a biomedical neuroscience researcher. “Are you going to the city?” asked an old man to Gaurav. He nervously responded, “No, I am just photographing the railway station.” “I want to go to the city,” said the old man. Seeing no one around and knowing that the time of the day meant no transport would be available to go to the city, Gaurav offered the old man a ride to the city.

They both settled into the car after Gaurav helped him put his luggage in. Gaurav introduced himself as a neuroscience researcher at the University of North Dakota, and the old man introduced himself as Inkyra and told him about how he had studied architecture at UC Berkeley. “My dad was an architect too”, responded Gaurav, and they engaged in a conversation. They talked about classical music, colonial architecture in India, and city planning. They discussed the inconveniences caused by the Amtrak station due to its location on the outskirts of the city. At the end of the ride, Inkyra shared with Gaurav that he lives with schizophrenia which he linked to his “adverse childhood experiences”. Gaurav also got to know from him that he is in the city only for a week. They shook hands as Gaurav dropped him off and told him to take care.

This chance encounter shifted something in Gaurav. After he went back home, he kept thinking about Inkyra. Next week, he went to the apartment where he had dropped him off, only to find out that Inkyra had left already. He gave his number to the housing manager, but to date, he has not heard back from either the manager or Inkyra.

Finding Inkyra

Hoping to run into him, Gaurav started visiting the Amtrak station regularly and, a while later, started going downtown. He never met Inkyra, but on his expeditions to find him, he met with many new experiences. At first, he realized how Inkyra was right in pointing out the remote location of the station, which excluded vulnerable people from accessing the basic facility of transport.

He also met many other people. He couldn’t help but notice the social location of these others – people from privileged backgrounds having families waiting to pick them up, or the means to call a taxi service. With trains passing the station only once at night, the bus station being really far away, and unfavourable weather conditions, people from the bottom of the social ladder, disabled, and disadvantaged were left stranded at the station.

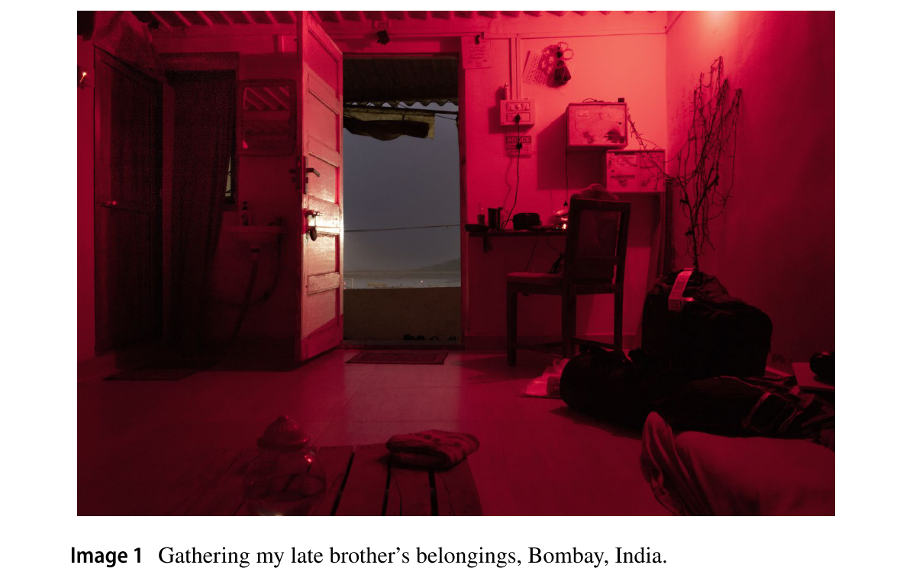

Gaurav helped such folks in every possible way, from giving his phone to them to make calls to getting them coffee and snacks. Sometimes, he also went back to check on them during lunch hours. His futile attempts to find Inkyra were accompanied by the memories of his brother. His brother, who passed away while navigating bipolar disorder. Gaurav notes,

“My repeated but futile searches for Inkyra were accompanied by memories of my caregiving experiences with my late brother—a forceful reminder of the sleepless nights I had waited up for him, imagining the worst possible outcome. At times, it was unclear whether I was searching for Inkyra or for my brother.”

Beyond Words: Invoking the Past as it Haunts Us

Primarily a biomedical neuroscience researcher, after the passing away of his brother in 2019, Gaurav Datta nurtured a deep passion to understand what it is like to live with a psychiatric diagnosis and its impact on familial relationships. In an attempt to understand mental illness, he took an ethnographic approach. Ethnography is an immersive study of people, beliefs, cultures, and places. For this work, he brought together three different perspectives of coproduction, autoethnography, and visual ethnography.

Coproduction refers to the creation of knowledge collaboratively with other stakeholders, including multiple voices in the knowledge production and understanding exercise. This often means creating knowledge with those affected by a diagnosis or a disaster, not just on them. Autoethnography can be understood as a combination of an autobiographical approach with ethnography, where the researcher connects their personal experiences with the wider socio-cultural and political context. Lastly, visual ethnography involves the use of visual material in ethnography, for example, photography, videography, etc.

To bring coproduction and auto-visual ethnographic method together to make sense of his past and present experiences about caring for people with mental illness, Gaurav uses a hauntological approach. Ideas of the past that continue to linger in the present, giving rise to a sense of “haunting,” are referred to as hauntology. The researcher uses hauntology both as a method and as a visual language.

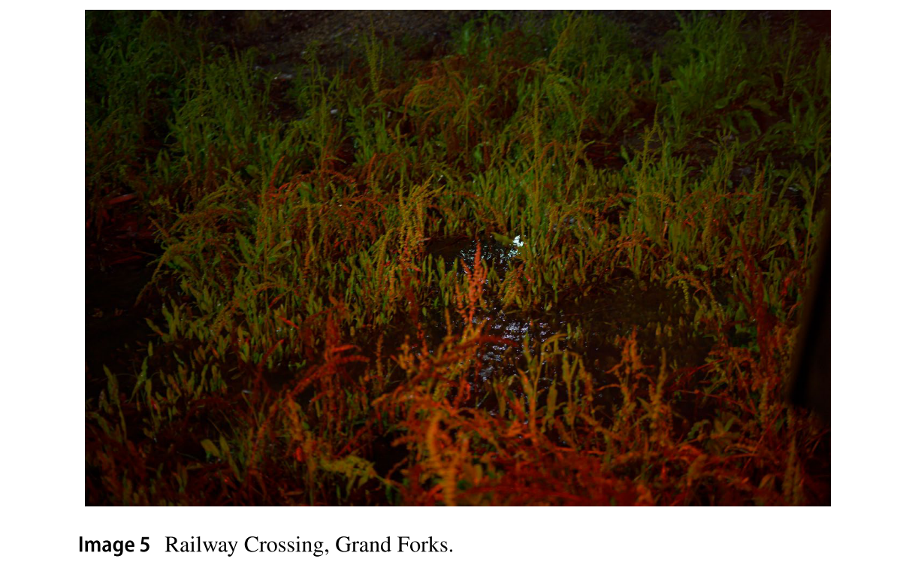

As a method, hauntology is used to make sense of his own lived experience of self-subjectivity as well as the inter-subjective relationships with his interlocutors (like Inkyra and his brother). As a visual language, he uses hauntology to translate his memories of past caregiving experience with his brother into present-day photographs. He does this because his past memories come up to the surface persistently and resist description through text. Moreover, these memories stay vivid as mental images. Here are the present-day photographs by Gaurav.

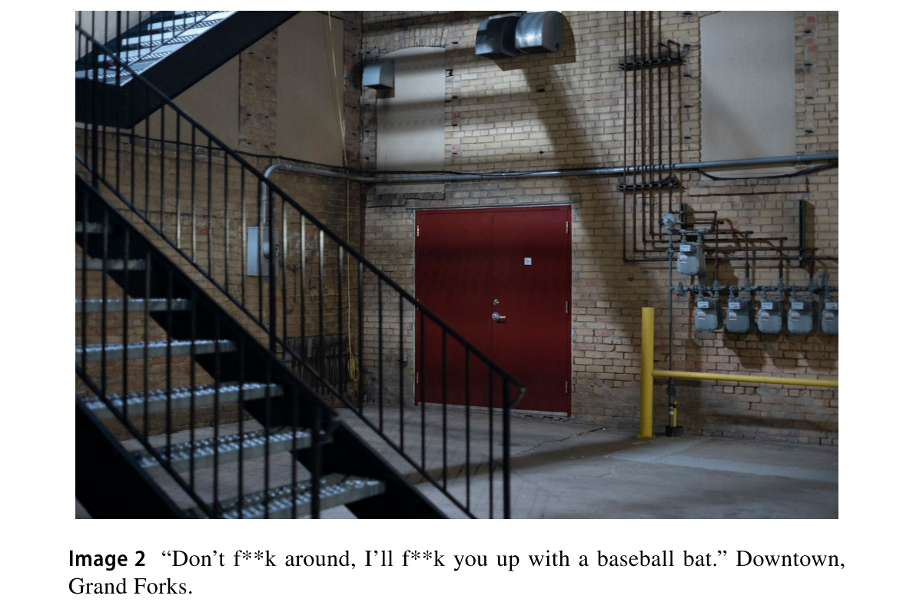

The present-day photographs tie several haunts that are all intersecting. It brings together the intense helplessness that he felt from several challenges he was facing in the past and the present like the pain of not being present for his brother in the final days due to his inability to travel, as well as the different forms of violence against people with mental illness, violence against outsiders (Gaurav himself felt like an outsider in North Dakota where he was stuck during his brother’s final days). Gaurav writes in his commentary,

“Under these circumstances, my mind conflated different forms of violence, and parts of my immediate surroundings acquired a ‘haunting’ presence, with me trying to find the real in the imaginary, and the imaginary in the real… Personally, the camera and the photographs became screens behind which I could conceal and reveal myself…”

After his chance encounter with Inkyra and later his absence, Gaurav’s view of the Amtrak station transformed. An ordinary place like the station revealed itself as haunting. Moreover, through his conversations with other people that he met at the Amtrak station, Grand Forks, North Dakota, he started situating the images of the station historically in its past.

The station

He found that the railway line on which the Amtrak ran was also used by BNSF, the Burlington National Santa Fe, and its predecessor, the Soo Line. These railway tracks had played a crucial role in the development of modern-day North Dakota while also facilitating the future trade of oil, coal, grains, and sugar beets through North Dakota. He notes,

“This period in history was associated with other forms of violence, associated with the arrival of settlers and land allotment through the Homestead Act of 1863. Thus, by denoting what is absent, the photographs are intended to act on multiple levels, tying the present to the past across personal, local, and historical levels.”

His meeting with Inkyra brought a change in his daily existence, forcing back his mental images, which informed his visual gaze. Visually, he used several different ways to represent the “haunting” experience. He included the use of colour, centering the images around the station and downtown to show his search for Inkyra as well as keeping the narrative arc of the photo sequence open-ended. He further mentions,

“Occupying this liminal world, the representative images are, however, elusive and imperfect; nevertheless, it still ties my past with the present in chaotic entangles, without a clear resolution.”

Conclusion

Gaurav Datta’s auto-visual ethnographic project is a creative example of a coproduction exercise. He created this project after his gaze shifted post his encounter with Inkyra, a stranger diagnosed with schizophrenia, which brought back his own past caregiving experiences for his brother, who passed away with bipolar disorder, as well as his present-day self, where he is haunted by the memories of the past in the present day of his life.

This project indicates that people’s meaning-making processes vary widely. Through this project, Gaurav shows how photography can help make sense of grief, care, and exclusion in everyday spaces, and how personal experiences can open new ways of doing mental health research.

References

Datta, G. (2025). The Elusive Image and the Missing Subject: A Hauntological Approach to Coproduction in Mental Health Research. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 1-11. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11013-025-09917-4

Researcher Contact Info: Gaurav Datta [[email protected]; [email protected]]

Neha Jain

Neha Jain is a doctoral scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Kanpur. In her doctoral work, she is exploring institutionalized and de-institutionalized mental healthcare settings in India to understand the nature of care and recovery in mental health through the experiences of various stakeholders. She is also a counseling psychologist trained in trauma-informed therapy and works through an attachment lens with people in their early adulthood years. Apart from therapy and research, she loves reading personal newsletters and listening to Desi rap music.