Last year I attended a prestigious international psychiatric conference at PGI Chandigarh, India, a medical school of considerable reputation in South Asia. The theme of the conference was public mental health. It was held over three whole days; 900 people from across the world had registered to attend, both face to face and virtually!

It was a star-studded event, with prominent figures from world psychiatry in attendance. This included Norman Sartorius (former director of the World Health Organization’s Division of Mental Health and former president of the World Psychiatric Association and of the European Psychiatric Association), Helen Herman (former president of the World Psychiatric Association), and Jonathan Campion (affiliated with UK’s NHS and advisor to the WHO). Elites of the global mental health movement such as Vikram Patel were also present and so were eminent Indian psychiatrists, especially from public sector teaching hospitals. Some, such as Patel, gave their talks virtually.

Having spent 10 years in the United States, I was well aware of the crises plaguing this discipline. I had become accustomed to news of the rampant abuses by the psy-disciplines (psychiatry, psychology, counseling), shady research practices, ineffective treatments and their adverse effects, scandals related to corruption and incompetence, unrelenting and misguided hubris, savage attacks from inside experts, and the discipline’s flailing excuses in the face of these embarrassments. I wasn’t sure what to expect from Indian psychiatry but I was not hopeful.

The reason I am writing about this conference—and why it’s relevant for a global audience—is because one of the leading trends in the psy-disciplines is the export of their knowledge and interventions to the rest of the world, especially low- and middle-income countries, alternatively known as the Global South. This is known as the Movement for Global Mental Health. When it emerged in early 2000s, it was brutally critiqued for its universalist assumptions and its tone-deafness to local realities. In response, the movement has taken a reflexive turn where it claims to have reformed itself. This conference allowed me to put those claims to the test. It also helped me observe the various iterations of psychiatry, how it changes shape and form, and how it is changed by indigenous knowledge.

In the end, I was both pleasantly surprised and eventually disappointed.

A Glimmer of Hope: Pharma on the Sidelines

As I entered the crowded makeshift courtyard to pick up my conference pass, I noticed multiple displays pointing to industry advertisements for numerous psychopharmaceuticals. I felt a tingle of excitement, a sense of a-ha! of a person who has caught red-handed someone they expected of grave wrongdoing. Stories of garish industry advertising and shady entertainment provided at early American Psychiatric Association (APA) conferences started running through my mind. Was I going to find attractive young women delicately touching the elbows of older eminent psychiatrists?

Thankfully, this was different, very different.

The pharmaceutical industry in this conference was treated like a creepy rich uncle who you must invite to the family reunion but then also strategically ignore. Unlike what I had read about the savviness of pharmaceutical representatives, reps here were only mildly interested in selling their products and knew even less about them. One rep told me “This is just the same drug with a different name. I don’t know why.”

The attendees of the conference seemed equally disinterested in pharma booths; however, I noticed that people frequenting these booths tended to be younger. Most hilariously, the pharma sessions were so sparsely attended that it almost made me feel pity for the presenters. At one session, I was the only real audience and the six other people in the room were all presenting a new medical device to each other.

Industry sessions were delegated to a separate building and took place in small, dingy rooms which were comically difficult to find. The session on an ADHD drug was on the wrong floor than the one specified in the conference pamphlet! Here is the kicker—or, as in Hindi we say, sone pe suhaaga—these sessions were scheduled during the lunch hour far away from the building where lunch was served.

In many medical conferences in the United States, industry sponsors fancy lunches and schedule their own sessions in the same hall at the same time ensuring maximum attendance. I feel that PGI’s status as a reputable public institute makes this distrust towards the industry understandable. Public sector doctors in India mostly prescribe drugs that are available in government clinics, making luring them with goodies rather difficult. Also, traditionally, there has been a suspicion of privatized healthcare (although this is rapidly changing in a neoliberal India) and associations with industry are frowned upon rather than seen as a symbol of status and repute.

Apart from sidelining the industry, the conference had other significant positive attributes. The public-sector Indian psychiatrists, who tended to be older, were deeply critical of overdiagnoses, overprescription, and polypharmacy, and instead spoke consistently about honoring a person’s story and not just seeing them as a set of symptoms.

“Look at the people—what diagnoses and what antidepressant—that’s all we do” was one such refrain. Another was: “Symptoms are a smoke-screen; look beyond the symptoms at the person.”

These speakers were cognizant of structural determinants of mental distress such as poverty, discrimination, and gender-based violence. A few openly and casually admitted that psychiatric diagnoses are simply provisional categories and “have no objective existence.” This claim was accepted without resistance among the rest of the panelists. I was left impressed, surprised, and mildly proud of my people and the work they do.

Additionally, the conference highlighted the work of numerous non-psychiatric, non-mainstream organizations that do trauma-informed work, provide financial and psychological help to the marginalized, mobilize legal resources for the victimized (mentally unstable people on death row), and so on. They discussed how psychiatric ignorance of comorbid physical issues often leads to misdiagnoses; for example, diagnosing children who have hearing or vision problems with dyslexia or ADHD.

One presenter openly addressed psychiatry’s role in torturing prisoners during Bush-era administration, centering a human rights approach towards patients. Another asserted that a person’s right to consent, dignity, and liberty trumps their right to treatment. A prominent female Indian psychiatrist spoke of medicalization of women’s problems, and how men often use psychiatric medication to quell to women’s legitimate responses to mistreatment and abuse.

Many South Asian psychiatrists spoke about the importance of good diet, healthy lifestyle, sleep, and exercise as central to mental health. “Everyone is into diagnoses and causes and not into helping and solving,” one speaker said. NGOs discussed systemic issues that cause psychological distress, such as inability to access government assistance for those who don’t have government IDs which leads to increased mental duress. Others noted the importance of building interventions based on what the community itself considers important and beneficial, not some outside experts.

After the first day, I was exhilarated. This was a place where structural determinants were featured front and center, where industry was treated like it was a dirty rag to be kept outside the house, and where overdiagnoses and polypharmacy were deeply problematized—all in a mainstream psychiatric conference! One wouldn’t be wrong in calling me giddy!

“It’s Complicated”: Empty Promises and Failed Agendas

By the second day, I started feeling something was amiss. Among the rhetoric on structural determinants (poverty, violence, exploitation, etc.) and how we must make care accessible to more people, no one clearly stated what this “care” was that merited desperate escalation. This is the central premise of the Movement for Global Mental Health—that limited and middle income countries are in abject need of psychiatric care but have a personnel shortage—a treatment gap. What was the treatment?

When I decided to ask this question individually to Jonathan Campion, he mumbled something about antidepressants, and how things are “complicated.” When I pushed about which “amazing treatments” needed scaling up and what about the role of culture-specific issues, I received a response that had multiple buzz-words but was essentially empty—how “antidepressants work right now but therapy takes time”, and how we need to improve primary care. Given that prominent experts have criticized both psychiatric screening and diagnoses by primary care physicians for leading to diagnostic inflation, this claim was a red flag.

The absurdity of fixing farmer suicides in India, caused by multiple systemic issues, with problematic antidepressants was probably not lost on them, which is why there was really no deep discussion on which treatments should be made affordable. This incited me to ask more presenters about the fixes we were offering for the systemic problems they had listed—over and over, I was told that things “were complicated.” This was a cop-out and it reminded me of Arthur Kleinman writing about numerous failures of the biomedical model and the gloomy future of academic psychiatry. He noted how embarrassing it was to hear psychiatrists hide behind “it’s terribly complicated.”

I spoke with other attending mental health professionals (not psychiatrists) who were similarly perturbed by the fact that no one was addressing deeply and fully what to do and how to help—interventions and treatments. Did we offer treatments that were as systemic as the problems we listed? Could we advocate for better policies and debt relief for farmers? If we can point to rabid capitalism and social alienation as possible causes of student burnout and suicide, then do we have treatments to address these causes? The answer I received was “we can’t do everything,” “this is a wide-ranging question,” “it’s a complex issue.” As if the problems we had been discussing were ever simple!

Behind progressive sounding buzz-words such as “community,” “structural,” and “accessibility” were empty promises and hollow reformations. There was also a real chance of harm! Mental health interventions cost resources. Is it fair to take away financial and medical aid in already resource-poor countries, and reroute it towards interventions that don’t fit the causes—interventions such as psychopharmaceuticals that are under fire for both inefficacy and adverse effects, and are premised upon theories that are now all but discarded? As Dian Million has pointed out, mental health interventions, even when they appear progressive with their purported trauma-informed practices, can still be used to undercut people’s actual needs. For example, native people’s demands for land and water rights in Canada were met with responses that the wronged must receive trauma counseling instead.

Others write that community mental health care workers in rural India have essentially become medication enforcers, regularly dismissing complaints from patients and families about inefficacy and side effects. Is this how the global mental health movement is filling the treatment gap—having non-expert workers cajole or threaten poor rural people into taking medication when many of them haven’t seen a real psychiatrist in two years? Administering dangerous drugs like clozapine without conducting required regular blood tests? In many parts of the Global South, the side effects of psychotropic drugs are even more devastating than they already are in modern Western societies. Physical strength allows people to herd animals, bring water to their village, and so forth, and the adverse-effects of antipsychotics such as dullness and excessive sleep threaten survival.

The conference was rife with discussions on stigma of mental illness, which is apparently much worse in the Global South (I sensed a hint of racism here). Nearly everyone mentioned how stigma stops people from seeking help, but no one noted that 1) the help we offer is not terribly safe or effective, 2) mental health stigma campaigns have been spectacular failures, and 3) biomedical psychiatric explanations have been consistently linked to worse stigma. The use of exaggerated statistics, and references to the problematic DALY index and the much-critiqued global burden of disease numbers seemed to point to a global emergency of mental health crisis. This was accompanied by stereotypical pictures of brown and black people, living in poverty, waiting for global saviors. I must mention here that the latter was specifically present in the talks of numerous international presenters (including Indian-origin ones) but thankfully absent from indigenous ones.

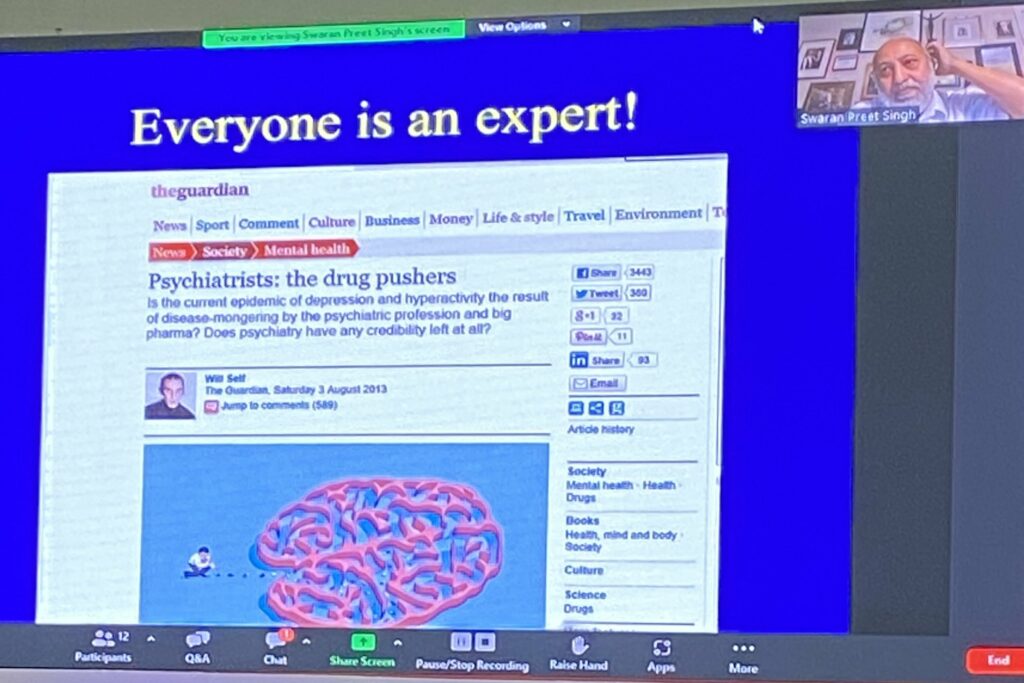

By the end of the third day, my enthusiasm had died and my hope was defeated. It was replaced with resignation, and occasional rage. This peaked with one of the final presentations by Swaran Preet Singh, a psychiatrist from the UK who considered any criticism of psychiatry to be propaganda. He even took issue with journalists writing about kickbacks and industry corruption in psychiatry, saying it was audacious that they thought of themselves as experts (The Guardian received special mention for such reporting).

Reiterating the now laughed-at diabetes metaphor (“mental illness is like diabetes that needs consistent management”), Singh admonished fellow psychiatrists for being internal critics of the discipline, and brought up Joanna Moncrieff and her writings as an example of what a traitor looks like. He clarified that psychiatrists have completely and fully answered all of anti-psychiatry’s questions and yet these critics still keep having issues.

At one point, Singh reiterated Ronald Pies’s disproven claim that no “well-informed” psychiatrist ever believed in the simplistic chemical imbalance theory by saying “I have never met a psychiatrist who said ‘oh, here comes a dysregulated dopamine receptor.’”

When I hear this dismissal from psychiatry, I am reminded of my American undergraduate students. I would ask them if they believed mental health problems were caused by faulty brain chemicals and most said yes. I would inquire who told them about this and most of them cited their primary care doctor or their psychiatrist. Lastly, we would discuss claims by psychiatrists denying that they ever believed in the chemical imbalance theory and I would watch betrayal dawn upon their faces as they realized that they had been lied to, and lied about. After Singh’s talk, there was absolute silence. I was pleased by how flat it fell on the audience.

What gave me hope was that indigenous public sector psychiatrists were deeply critical of the harms and transparent about the limitations of their discipline. They were cognizant of, and sensitive to the realities, of their communities. I am aware that this critical attitude is fast vanishing among the younger generation and private physicians. My colleagues in community healthcare often shared horror stories of meeting patients who had been prescribed 10ish drugs by their provider. This sensitivity was also absent in the international presenters who comfortably fell back into the white savior mode, flanked by pictures of “depressed” brown kids in refugee camps.

As I said at the start of this essay, this experience is not simply about a conference, but is reflective of a wider reflexive and reformative turn that the movement for global mental health says it has taken. In the face of multiple criticisms, the movement decided to incorporate structural determinants, cultural sensitivities, and dialogue with communities into its practices. I believe this is putting lipstick on a pig.

Unless we are open about the grave limitations of our treatments, like some global mental health advocates such as Kleinman have admitted to, we are putting band-aids (toxic band-aids?) on a gaping wound. Unless we decide to find solutions that are as complex and systemic as the problems we discuss, the claims of reformation are nothing more than empty promises. Unless we stop hiding behind phrases such as “it’s complicated,” we will remain an embarrassment. And no amount of forced internal agreement will save us from that.

Dr. Ayurdhi Dhar is a spotlight interviewer for Mad in America and the founder of Mad in South Asia. She does some professoring (Assistant Professor at the University of West Georgia) and academic writing (author of Madness and Subjectivity: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Psychosis in the West and India), but mostly likes to be known for her love for food, animals, friends, and family. She struggles daily with her desire to pet every dog she sees.